Sodom’s Big Bang: Caused by Meteor or Earthquake?

Deborah Hurn | January 21, 2022 | News

Résumé : Sodome était-elle dans la vallée du Jourdain, et ce site a-t-il été détruit par une explosion cosmique ? Dans la deuxième partie de cette série en deux parties, nous examinons des preuves provenant de l’intérieur et de l’extérieur de la Bible pour nous rapprocher du véritable emplacement de la destruction spectaculaire de Sodome.

Alors le Seigneur fit pleuvoir sur Sodome et Gomorrhe du soufre et du feu du Seigneur, du haut du ciel. – Genèse 19:24 (NRSV)

Indices bibliques sur la localisation de Sodome

Quelques années avant leur ardent chambardement, les cinq villes de la plaine avaient été conquises par une alliance de quatre rois du Nord, dirigée par Chedorlaomer d’Elam, qui furent à leur tour poursuivis et vaincus près de Damas par Abram et son armée privée. Ce récit est riche en données géographiques, tout comme le récit de la traversée par Israël de la vallée méridionale du Jourdain sur son chemin vers Canaan, quelque quatre cents ans plus tard. Ces deux récits contribuent à compléter le « dossier » sur l’emplacement de Sodome et doivent être pleinement pris en compte, tout comme les détails de la destruction.

Les 4 Rois du Nord

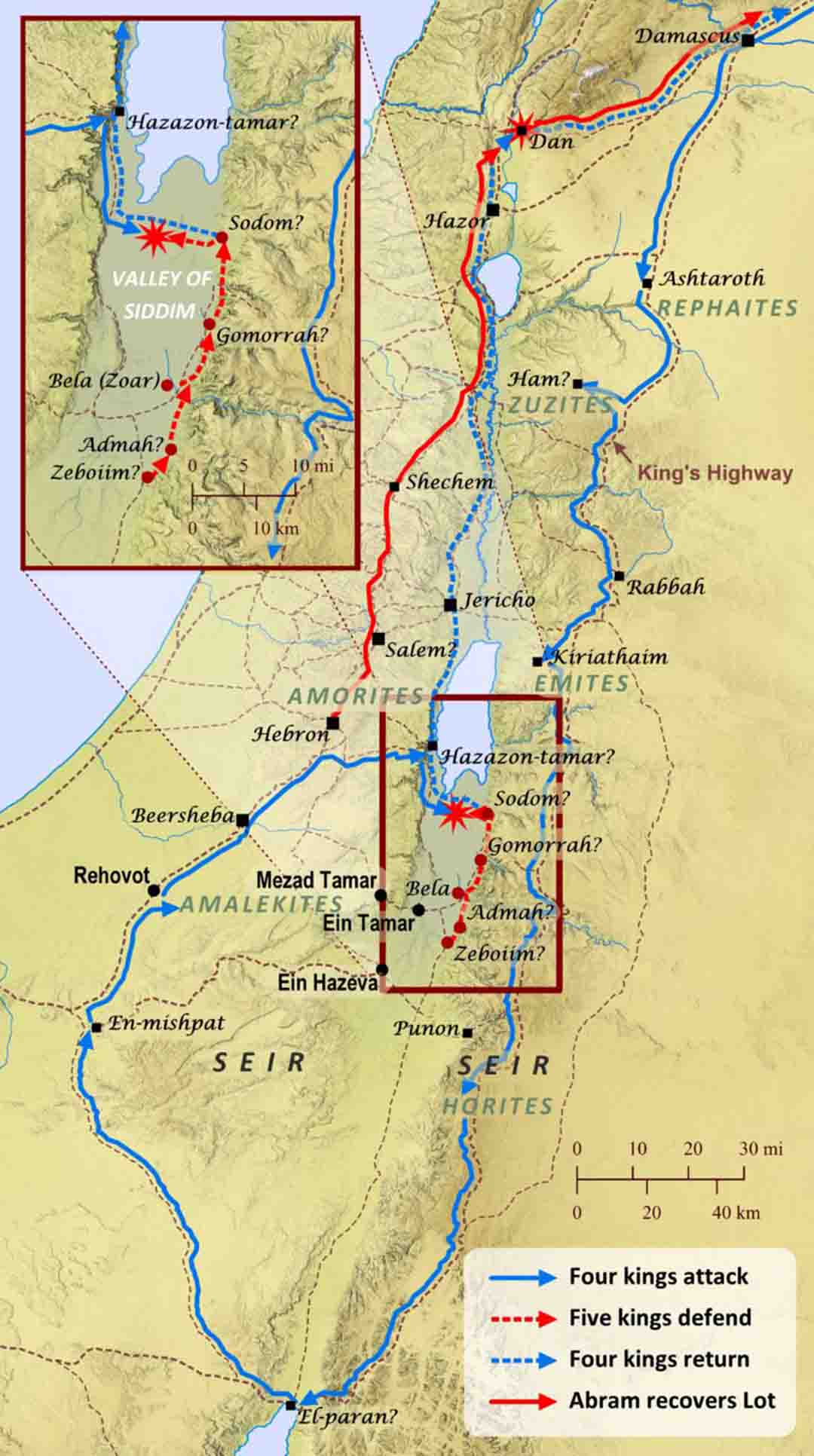

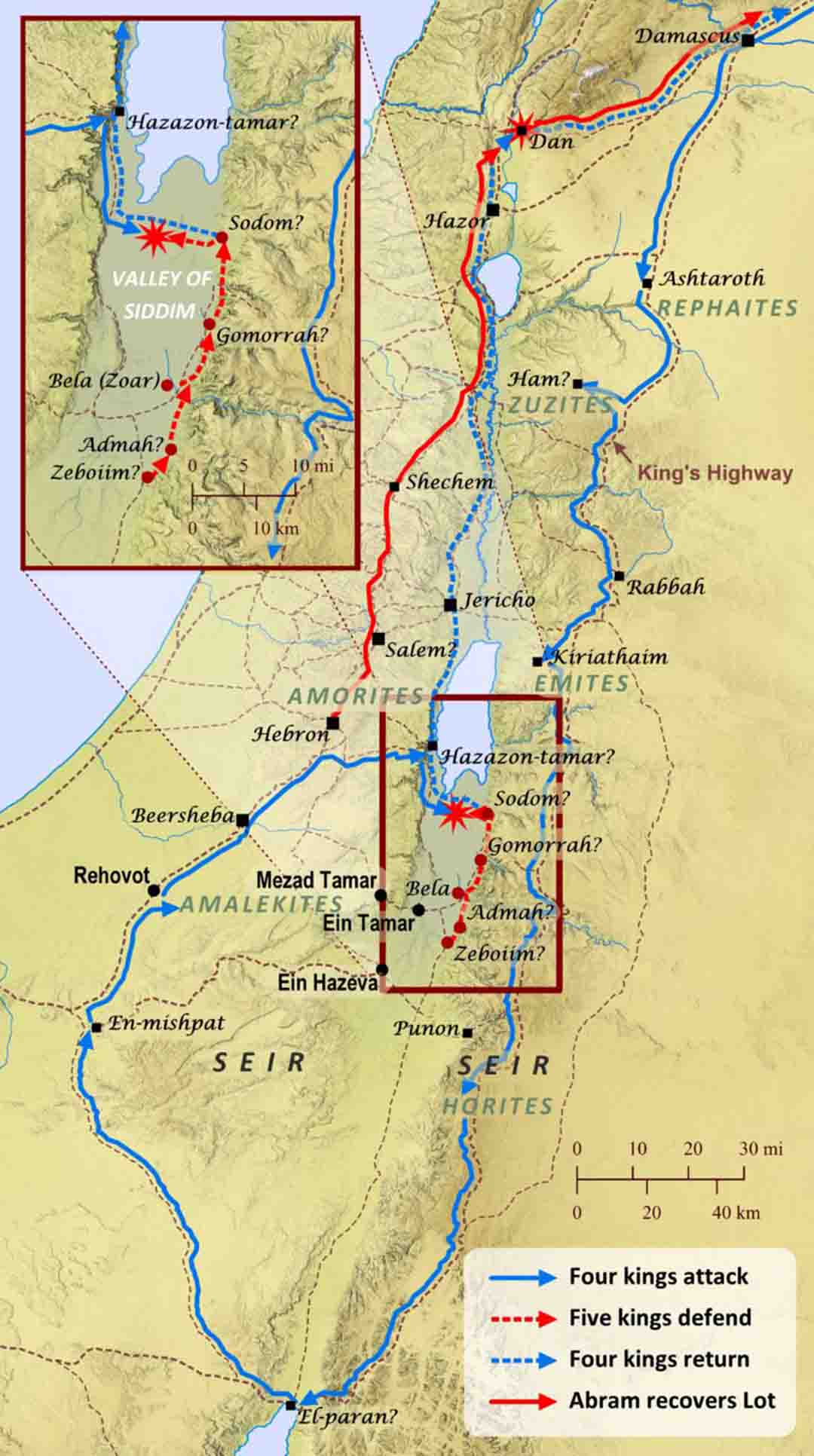

David Barrett, du blog Bible Mapper, a récemment publié un article sur » La bataille de la vallée de Siddim « [1]. Sa carte est arrivée juste à temps pour que je corrige une section de ma thèse sur les régions géographiques des voyages israélites pour laquelle j’ai dû prendre en compte la campagne de Genèse 14 parmi d’autres données bibliques.

Jusqu’à ce que je voie la carte de Barrett, j’avais accepté le point de vue d’Aharoni selon lequel les quatre rois du Nord, après avoir conquis les Amalécites à Cadès, ont pris la route ENE (Est-Nord-Est) à travers Nahal Zin vers le nord de la Arabie et de là vers le nord pour affronter le roi de Sodome et ses alliés dans le Ghor ( » plaine engloutie « ) au sud de la mer Morte[2]. Ein Hazeva (Ain Husb) dans le nord de l’Arabah, parfois identifiée comme la Thamara classique[4], correspond mal à la Hazazon-Tamar biblique car elle se trouve à environ 15 km au sud de l’entrée de Nahal Zin dans l’Arabah. Conformément à l’itinéraire des rois du nord de Kadesh à la mer Morte, Hazazon-Tamar est souvent identifié plus au nord à Ein Tamar (Ain el-Aros, » source du palmier « ) [5] dans le cône alluvial de Nahal Zin à l’entrée de l’Arabie.

Si, au contraire, Hazazon-tamar est Ein-guedi selon 2 Chroniques 20:2, il y a un problème logique avec la séquence de la campagne. Si l’on s’approche du sud, Ein-Guedi, sur le côté ouest de la mer Morte, se trouve bien au-delà des emplacements traditionnels des villes de la plaine, de sorte que les envahisseurs devraient rebrousser chemin pour livrer bataille aux cinq rois. De plus, la nécessité pour le roi de Sodome de sortir pour combattre si les envahisseurs l’avaient déjà dépassé semble douteuse.

Des messagers vinrent dire à Josaphat : « Une grande multitude vient contre toi d’Édom, d’au-delà de la mer ; ils sont déjà à Hazazon-tamar » (c’est-à-dire En-gedi). – 2 Chroniques 20:2

La suggestion de Barrett que les envahisseurs ont approché de l’ouest à travers le Néguev du nord directement à Ein-guedi a fait plus de sens. Je lui ai communiqué que je serais heureux de ne pas avoir à expliquer comment les quatre rois voyageant vers le nord à travers l’Arabah pourraient être arrivés à Ein-guedi avant d’attaquer les cinq rois au sud de la mer Morte. Il m’a expliqué qu’il avait jeté un tout nouveau regard sur Genèse 14 après avoir lu que tout le bassin sud de la mer Morte était probablement sec pendant cette période.

La carte de Barrett représente une toute nouvelle compréhension de l’événement, par rapport à la carte qu’il a créée pour le Crossway ESV Bible Atlas de 2010, plaçant Hazazon-tamar à l’un des emplacements du nord de l’Arabie suggérés pour la Thamara classique.

L’itinéraire qu’il propose de Kadesh (Ein Qudeirat) à Hazazon-tamar (à Ein-guedi) pénètre et traverse le Néguev septentrional (les bassins de Beersheba et d’Arad) du sud-ouest au nord-est en suivant la section orientale du chemin de Shur. Il s’agit du même itinéraire que celui emprunté plus tard par les douze espions israélites de Cadès vers Hébron sous la direction de Moïse (Num. 13:2, 17-22). Les espions ont ensuite continué vers le nord le long du Pays des Collines jusqu’au Liban (v. 21).

Selon le nouvel itinéraire de Barrett, les quatre rois du nord de l’époque d’Abram [8] contournèrent Hébron, continuèrent vers le nord-est par l’escarpement de la mer Morte et descendirent jusqu’à Hazazon-tamar à En-Gedi. Après avoir conquis tous les peuples sur leur chemin, tant du côté de la Transjordanie que du côté du Néguev de la vallée du Rift, sans doute pour isoler Sodome de ses voisins, l’armée alliée débouche sur le côté sud-ouest du bassin de la mer Morte, face aux villes de la plaine, de l’autre côté de la vallée de Siddim.

J’ai fait remarquer à David qu’après avoir vaincu Sodome et capturé Lot, les envahisseurs ne seraient pas montés sur les hauts plateaux cananéens (comme indiqué sur la carte de son blog) car il n’y a aucune trace de leur conquête des nations de la Cisjordanie, contrairement à la Transjordanie où leur conquête des nations indigènes du plateau est répertoriée par nation et par capitale (Gen. 14:5-7)..

Le récit ne dit pas que les quatre rois sont passés par Salem (Jérusalem), mais seulement qu’Abram et ses hommes sont revenus par là après les avoir poursuivis et vaincus près de Damas et avoir récupéré les captifs et le butin (vv. 17-24). Ainsi, les quatre rois du nord, ayant atteint leur objectif de soumettre la région de Sodome, se sont probablement dirigés vers le nord le long du côté ouest de la mer Morte et de la vallée du Jourdain jusqu’à Dan, retournant à leurs royaumes dans la région du Haut-Euphrate [9].

David a rapidement créé une nouvelle version de sa carte pour moi, en changeant le cours du voyage de retour des quatre rois. Pour des raisons de comparaison avec sa nouvelle proposition d’avancée à travers le nord du Néguev, il a ajouté la route de Wadi Zin de Kadesh à l’Arabah. Sur le chemin du Shur, il a également marqué la station intermédiaire de Ruheibe, aujourd’hui Rehovot ba-Negev, qui était le lieu probable de la rencontre d’Elie (bien plus tard) avec un ange, à une journée de voyage dans le désert au sud de Beersheba, en direction du mont Horeb (1-Rois 19:1-8). Nous avons discuté de l’article de Laudien, mais Barrett n’a relocalisé aucune des cinq villes de la Plaine, vraisemblablement par manque de preuves archéologiques.

La carte qui en résulte est à la fois familière et surprenante ; la civilisation de Sodome se trouve dans le lieu traditionnel au sud de la mer Morte, mais l’expédition de Chedorlaomer contourne tout le district de Sodome à une grande distance, un peu comme des loups qui encerclent un troupeau. Plus important encore, seule cette nouvelle proposition d’itinéraire donne un sens géographique à la connexion entre Hazazon-tamar et Ein-guedi.

Tremblements de Terre !

La mer Morte elle-même est un élément de la principale ligne de faille afro-asiatique qui s’étend du Kenya vers le nord, en passant par la mer Rouge et son bras oriental (le golfe d’Aqaba), la vallée de l’Arabie, la mer Morte, la vallée du Jourdain, la mer de Galilée et la vallée de la Hulah, jusqu’à ce qu’elle se termine au Levant.

La vallée du Rift et ses nombreuses ramifications ont connu de nombreux tremblements de terre au cours de la période biblique [10] . Dans la Bible hébraïque, les tremblements de terre semblent avoir joué un rôle dans la traversée de la Mer Rouge (Ps. 77:17-20 ; 114), le déploiement du Sinaï (Ex. 19:18), la terre qui a « avalé » Koré (Num. 16:31-33), la conquête de la Transjordanie (Judg. 5:4-5 ; Ps. 68:7-8), la traversée du Jourdain (Jos. 3:15-17 ; Ps. 114), la chute de Jéricho (Jos. 6:20), l’épreuve d’Elie au mont Horeb (1 Rois 19:11-12), et le jugement sur Israël et ses voisins (le tremblement de terre du roi Ozias, Amos 1:1 ; 9:1 ; Zach. 14:5).

Dans la Bible grecque (soutenue par de nombreuses prophéties hébraïques, par exemple Zach. 14:3-4), des tremblements de terre accompagnent la crucifixion et la résurrection de Jésus (Matt. 27:50-51 ; 28:2), la conquête romaine de la Judée (Matt. 24:7), et la destruction de Babylone la Grande en tant que « Sodome » des temps modernes (Luc 17:29-30 ; Apoc. 11:13 ; 16:18 ; 18:17-18).

La politique d’intervention divine tout au long de l’histoire biblique semble être « Ne jamais laisser un bon tremblement de terre se gaspiller ». Pourquoi la cause de la destruction de Sodome – la catastrophe naturelle originelle de la longue saga hébraïque – ferait-elle exception ?

La Destruction de Sodome

L’explication traditionnelle de la destruction de Sodome implique un tremblement de terre dans la vallée du Rift, provoquant une explosion souterraine qui enflamme le bitume et fait pleuvoir du soufre et du sel brûlants sur la région environnante (cf. Deut. 29:23 ; Luc 17:28-29).

La combustion de grands dépôts (naturels) d’hydrocarbures stockés a probablement créé un affaissement de la région, suivi d’une augmentation à long terme du niveau et de l’étendue de la mer Morte, dont l’eau hyper-salée a ensuite recouvert tous les vestiges des villes anciennes.

Comme quatre des cinq villes de la plaine ont été totalement détruites lors de cet événement, il est raisonnable de conclure que Sodome, Gomorrhe, Admah et Zeboiim se trouvaient toutes dans le bassin sud de la mer Morte, bien que ces deux dernières ne soient pas mentionnées nommément dans le contexte de la destruction. Les bassins nord et sud de la mer Morte ont continué à s’affaisser[11].

Le bitume, le soufre et le sel se manifestent principalement le long du côté sud-ouest de la mer Morte ; en fait, Har Sedom (nom conservé en arabe sous le nom de Jebel Usdum) est un dôme de sel de 11 km de long. Dans cette région, le pilier de sel populairement connu sous le nom de « femme de Lot » surplombe la route 90 qui s’étend du nord au sud le long de la rive occidentale de la mer Morte.

Laudien note que de tels dépôts ne se trouvent pas dans le nord ou le sud-est de la région de la mer Morte.[12] Comme le conclut Albright, « Le seul emplacement possible pour la vallée de Siddim, avec ses puits d’asphalte (rendus « slime-pits » dans l’AV) est dans la partie sud-ouest de la mer Morte. » [13]

Les détails du récit de la Genèse soulignent la proximité de Zoar et de Sodome (Gen. 19:17, 25, 28). Ayant fui Sodome juste avant l’aube, Lot et ses filles sont arrivés à Zoar peu après le lever du soleil (19:15, 17-23). Zoar a peut-être échappé à la conflagration parce qu’il n’y a pas de bitume au sud-est de la mer Morte.

Les dômes de sel indiquent souvent des réservoirs souterrains de gaz naturel piégé[14]D’après la description biblique, Wood conclut que le moyen de destruction de Sodome a été une explosion et une tempête de feu :

« Une explication possible de la destruction des villes de la plaine est que la pression d’un tremblement de terre a fait remonter des produits pétroliers inflammables souterrains à travers les lignes de faille. Ils se sont alors enflammés et se sont abattus sur la campagne environnante »[1].

Wood note également que les mots spécifiques pour » fumée » קִיטֹר qiytor et » fourneau » כִּבְשָׁן kivshan indiquent un fort courant d’air ascendant typique de celui d’un conduit de fumée (Gen. 19:28). Il est important de noter que les détails du soufre et du feu (matière brûlante) pleuvant d’en haut et de la fumée épaisse forcée vers le haut ne correspondent pas aux effets de vaporisation instantanée d’un » flash » surchauffé du type proposé.

Si l’on veut localiser et expliquer un événement selon le récit biblique, il est certain que toutes les données bibliques doivent être prises en compte dans l’hypothèse.

Bill Schlegel, author of the Satellite Bible Atlas,[16]says:

Je crois que nous aurons toujours des problèmes pour essayer de localiser Sodome et Gomorrhe. En plus des changements géologiques/géographiques significatifs de la région associés à la destruction divine (Gen. 13:10), la destruction divine n’a probablement pas laissé beaucoup de trace (aucune ?) de ces villes à découvrir. L’hébreu pour la destruction de ces villes est unique (une combinaison de shachet « détruire » et hafach, « mettre à l’envers »). Il est peu probable que l’un de ces tells/ruines dans le Rift (au nord ou au sud) soit Sodome ou Gomorrhe. Il est plus probable que ces ruines représentent des villes périphériques, dont l’une était peut-être Zoar, qui ont été épargnées par le jugement divin[17].

D’autre part…

There are some ‘cons’ for the traditional scenario, some logical, some chronological:

- Le niveau de la mer Morte a considérablement baissé ces dernières années, entraînant un rétrécissement du bassin sud. L’exploration et l’activité extensives dans la région n’ont produit aucune preuve indiquant l’existence de sites antiques[18]Il est toutefois possible que le dépôt constant de sel et de limon par les rivières entrantes ait recouvert le fond de la vallée depuis les temps anciens[19].

2. Pour autant que les archives historiques le révèlent, et malgré de nombreux tremblements de terre le long de la vallée du Rift au cours de la période biblique, un événement cataclysmique du type de celui rapporté dans Genèse 19 ne s’est pas reproduit. Cela pourrait simplement indiquer que le combustible souterrain a été largement épuisé lors de la conflagration de Sodome, ou que d’autres conditions nécessaires, telles que le tremblement de terre et le climat, n’ont pas été réunies.

3. Les principaux candidats pour Sodome et Gomorrhe sur le côté sud-est de la mer Morte – Bab adh-Dhra et Numayra – ont été détruits dans une tempête de feu à la fin de l’âge du bronze précoce III, trop tôt pour l’ère d’Abraham dans le bronze moyen I selon la chronologie standard.[20] Quant à Ein-guedi sur le côté sud-ouest, il y a des preuves pour seulement trois périodes majeures de peuplement – Chalcolithique, âge du fer et romain – aucune d’entre elles ne correspond à l’époque d’Abraham. John Osgood explore les implications radicales de l’identification de la civilisation chalcolithique du nord du Néguev avec les Amorites de Hazazon-tamar du vivant d’Abraham,[21] un changement qui alignerait également l’effondrement de l’âge du bronze précoce II-III en Cisjordanie (Canaan) et en Transjordanie (Bashan, Ammon, et Moab) avec la conquête israélite.[22]Une telle proposition ouvre encore un autre front controversé dans le débat sur Sodome. Il suffit de dire qu’aucun des deux scénarios n’a le soutien de l’archéologie conventionnelle qui considère l’ère chalcolithique comme préhistorique, l’EBA comme prébiblique et l’âge du fer comme israélite (donc bien après l’époque d’Abraham).

Le sud de la vallée du Jourdain et l’identification de Tall al-Hamman

Quelque 400 ans après l’alliance d’Abraham, ses descendants, les Israélites, sont revenus d’Égypte vers Canaan en passant par le Sinaï et la Transjordanie (Gn 15, 13-16 ; Judg 11, 15-22). Leur dernier campement avant de traverser en Canaan se trouvait dans les » plaines de Moab « , » sur le Jourdain [de] Jéricho » יְרֵחֽוֹ עַל-יַרְדֵּן al-yarden yeriho (Num. 26:3, 63 ; 31:12 ; 33:48-50 ; 35:1 ; 36:13), ou « de l’autre côté du Jourdain [de] Jéricho » יְרֵחֽוֹ לְיַרְדֵּן מֵעֵבֶר me-ever le-yarden yeriho (Num. 22:1 ; Josh. 13:32), cette dernière référence précisant également » vers l’est » מִזְרָחָה mizrahah.

L’emplacement de leur camp est triangulé entre trois points, tous des villes – Jéricho, Beth-jeshimoth et Abel-shittim (Nombres 33, 48-49). Jéricho (Tell es-Sultan) se trouve sur le côté ouest de la vallée méridionale du Jourdain, tandis que Beth-jeshimoth (nom conservé sous le nom de Tall Azaymah) se trouve près de la rive nord de la mer Morte. Abel-shittim, par conséquent, correspond le mieux à l’emplacement de Tall al-Hammam sur le côté est de la vallée, presque directement en face de Jéricho[23]Il est évident qu’Israël a confiné son camp à la partie la plus méridionale de la vallée, peut-être à cause des Ammonites dans la vallée centrale du Jourdain près de l’embouchure du Jabbok.

L’expression « plaines de Moab » est une traduction courante de aravoth moav מוֹאָב עַרְבוֹת, une zone de steppe au-dessus du fond de la vallée du Jourdain pouvant atteindre 8 km de large avec une altitude de 300-200 m bsl. Il existe des « plaines de Jéricho » correspondantes de l’autre côté du Jourdain (Josh. 4:13 ; 5:10 ; Jer. 39:5 ; 52:8 ; 2 Kings 25:5), un peu plus étroites et irriguées par moins de rivières pérennes. Entre les deux, le Jourdain coule à environ 380-390 m d’altitude.

Les rives du lit du fleuve, surnommées par les prophètes geon ha-yarden הַיַּרְדֵּן גְאוֹן « la fierté du Jourdain » (Jér. 12:5 ; 49:19 ; 50:44 ; Zach. 11:3), entretiennent de profonds fourrés de tamaris, de saules, de peupliers, de lauriers-roses, de cannes et de roseaux. Entre les rives luxuriantes du fleuve et les « plaines de Moab » d’un côté et les « plaines de Jéricho » de l’autre, on trouve plusieurs kilomètres de hauts monticules érodés de barriques.

Au total, le sud de la vallée du Jourdain s’étend sur 22 km à son point le plus large, de l’arrivée de l’oued Qelt à l’ouest (d’où Jéricho) à l’arrivée de l’oued Sir-Kafrayn à l’est (d’où Abel-Shittim), et sur environ 20 km de long, du cône alluvial de l’oued Shuayb au nord au rivage de la mer Morte à l’est.

Cette région basse et ensoleillée présente de nombreuses traces d’occupation humaine depuis les temps les plus reculés. L’Écriture fait fréquemment allusion aux sites cultuels « beth-/baal- » sur les pentes orientales du sud de la vallée du Jourdain : Bamoth-baal (Nombres 22:41 ; Inscription Moabite [MI], ligne 27) ; Beth-/Baal-peor (Deut. 3:29 ; 4:46), Beth-jeshimoth (Josh. 13:18-20 ; Ezek. 25:9) ; Beth-/Baal-meon (Nombres 32:37-38 ; Jer. 48:1, 23 ; Ezek. 25:9 ; MI, lignes 9-10) et Beth-arabah sur le Jourdain (Josh. 15:61).

A cela s’ajoutent les noms de villes de toutes époques situées dans et autour du sud de la vallée du Jourdain : (Abel-)Shittim (Num. 33:49 ; Josh. 2:1), Kiriathaim (Num. 32:37 ; Josh. 13:19 ; MI, lignes 9-10), Elealeh, Sibmah/Sebam, Nebo (Num. 32:3, 37 ; Isa. 16:9 ; MI, ligne 14), et, du côté ouest, Jéricho (par exemple 2 Rois 2:5). Il est donc révélateur que pas une seule fois dans les récits bibliques de l’activité des Israélites dans la vallée méridionale du Jourdain et de leurs voyages à travers celle-ci (par exemple, 2 Sam. 17:16 ; 2 Rois 25:5), les textes ne font référence à l’une des cinq villes de la plaine, pas même sous une forme telle que « le lieu qui était autrefois connu sous le nom de Sodome » ou « les champs de Gomorrhe ». Dans la géographie historique d’Israël et de la Jordanie, l’absence de preuve compte, en fait, comme une preuve d’absence, car la région est petite, les traditions bibliques tirent de longs fils, les données sont nombreuses et de nombreux noms sont conservés en arabe jusqu’à l’époque moderne.

Conclusion

Quelle que soit la vérité historique concernant la frappe d’un météore et l’explosion d’un avion à Tall al-Hammam, Sodome ne se trouvait pas dans le sud de la vallée du Jourdain. Les arguments en faveur de la localisation des cinq villes de la plaine au nord de la mer Morte sont en contradiction avec le scénario général. Selon les données géographiques bibliques, Sodome se trouve au sud et non à l’est de Jérusalem (Ezek. 16:46), près du site de Zoar (Gen. 19:20-22), et à portée de vue de Hazazon-tamar à En-gedi sur la rive occidentale de la mer Morte (2 Chron. 20:2).

Les preuves byzantines et médiévales de l’emplacement de Zoar sur la rive sud-est de la mer Morte s’accordent bien avec le récit de la Genèse. Il en va de même pour l’identification par les Chroniques de Hazazon-tamar à En-gedi sur la rive sud-ouest (2 Chron. 20:2 cf. Gen. 14:7-8), un détail qui concorde avec les premiers historiens qui relient systématiquement En-gedi à la région de Sodome. Le soutien de Laudien à la vision classique et la révélation de Barrett concernant l’itinéraire des envahisseurs de Cadès à Hazazon-Tamar expliquent ensemble toutes les données bibliques, historiques et géographiques, sinon les données archéologiques connues jusqu’à présent.

Collins a proposé d’identifier Sodome comme étant Tall al-Hammam vers 2009. Réalisant que la probabilité d’une conflagration bitumineuse dans cette région était faible ou absente, lui et ses collègues ont ensuite proposé une autre cause de destruction catastrophique. Cependant, leur hypothèse d’une explosion d’air météorique semble beaucoup moins probable qu’une explosion d’hydrocarbures provoquée par un événement sismique. Avec la présence abondante de bitume, de soufre et de sel dans et autour du bassin sud de la mer Morte, et avec le passage de la grande faille afro-asiatique au centre de la vallée du Rift, il n’est pas nécessaire de postuler un autre type de cataclysme. Tall al-Hammam est presque certainement la ville biblique d’Abel-shittim, l’une des nombreuses villes détruites à la fin de l’âge du bronze moyen en Israël et en Jordanie.

La théorie de Collins et de ses collègues d’une explosion météorique ne rend pas compte de plusieurs détails spécifiques du récit biblique : la pluie de matières brûlantes, de soufre et de sel ; l’emplacement des dépôts de bitume ; la fuite de Zoar malgré sa proximité avec Sodome ; et l’identité d’Hazazon-tamar à En-gedi. Lorsqu’on est confronté à des hypothèses concurrentes expliquant le même événement ou effet, il faut choisir la solution qui répond au plus grand nombre de critères tout en s’appuyant sur le moins d’hypothèses possible.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

END NOTES

[1] David P. Barrett, “The Battle at the Valley of Siddim,” Bible Mapper (blog), July 19, 2021, https://biblemapper.com/blog/index.php/2021/07/19/the-battle-at-the-valley-of-siddim/.

[2] Yohanan Aharoni, “Tamar and the Roads to Elath,” Israel Exploration Journal 13, no. 1 (1963): 31-34.

[3]C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, The Wilderness Of Zin (Archaeological Report), vol. 1914–1915, Annual (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1914), 71.

[4] Aharoni, “Tamar and the Roads to Elath.”

[5] With palms common from Jericho to Zoar (Deut. 34:3), the name is not indicative of the biblical site. In the Mishnah, Zoar is called ‘the City of Palms’ (Yevamot 16, 6).

[6] Yizhar Hirschfeld, “The Nabataean Presence South of the Dead Sea: New Evidence,” in Crossing the Rift: Resources, Routes, Settlement Patterns, and Interactions in the Wadi Arabah, ed. Piotr Bienkowski and Katharina Galor, Levant Supplementary Series 3 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2006), 170.

[7] David Neev and Kenneth O. Emery, The Destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah, and Jericho: Geological, Climatological, and Archaeological Background (New York: Oxford University, 1995), 62.

[8] Later renamed Abraham (cf. 17:5).

[9] Perhaps Melchizedek met and blessed Abram in thanks for preventing the northern kings from entering Canaan.

[10] Gary Byers, “Jordan River Valley, Jordan River and the Jungle of the Jordan,” Associates for Biblical Research, June 6, 2007, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3844-the-jordan-river-valley-the-jordan-river-and-the-jungle-of-the-jordan.

[11] Neev and Emery, Destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah, and Jericho, 123–24.

[12] Marcus Laudien, “Sodom and the Dead Sea,” The Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 9 (2002): 88.

[13] William F. Albright, “The Archaeological Results of an Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 14 (1924): 9.

[14] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/salt-dome

[15] Bryant G. Wood, “The Discovery of the Sin Cities of Sodom and Gomorrah,” Associates for Biblical Research 12, no. 3 (Summer 1999): 67–80.

[16] William Schlegel, Satellite Bible Atlas: Historical Geography of the Bible (Israel, 2012).

[17] Bill Schlegel, “Biblical Problems with Locating Sodom at Tall El-Hammam,” BiblePlaces (blog), January 4, 2012, https://blog.bibleplaces.com/2012/01/biblical-problems-with-locating-sodom.html.

[18] Primary sources are detailed in: Wood, “Discovery of the Sin Cities.”

[19] Albright, “Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea,” 8.

[20] Wood, “Discovery of the Sin Cities.”

[21] A. J. M. Osgood, “The Times of Abraham,” EN Tech 2 (1986): 77–87 https://creation.com/the-times-of-abraham.

[22] A. J. M. Osgood, “The Times of the Judges—The Archaeology: (A) Exodus to Conquest,” Journal of Creation 2, no. 1 (April 1986): 56–76 http://creation.com/the-times-of-the-judges-the-archaeology-exodus-to-conquest.

[23] For a compilation of references, see David E. Graves and Scott Stripling, “Identification of Tall El-Hammam on the Madaba Map,” Biblia | Sermons and Biblical Studies (blog), accessed October 29, 2021, https://www.biblia.work/sermons/identificationof-tall-el-hammam-on-the-madaba-map/.

[24] Menashe Har-El, “The Pride of the Jordan: The Jungle of the Jordan,” Biblical Archaeologist 41, no. 2 (1978): 67–68.

TOP PHOTO: Sodom and Gomorrah Afire by Jacob de Wet II, 1680. (credit: Daderot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

NOTE:

Tous les points de vue exprimés par les chercheurs qui contribuent aux articles du Thinker ne reflètent pas nécessairement les opinions de Patterns of Evidence. Nous incluons les points de vue de diverses parties des débats sur les questions bibliques afin que les lecteurs puissent se familiariser avec les différents arguments en jeu. – Continuez à réfléchir !

English version

Sodom’s Big Bang: Caused by Meteor or Earthquake? (Part 2)

Deborah Hurn |

January 21, 2022 | News

Summary: Was Sodom in the Jordan Valley, and was this site destroyed by a cosmic airburst? In Part 2 of this 2-part series we consider evidence from inside and outside the Bible to close in on the true location of Sodom’s spectacular destruction.

Then the Lord rained on Sodom and Gomorrah sulfur and fire from the Lord out of heaven. – Genesis 19:24 (NRSV)

Biblical Clues to Sodom’s Location

Some years before their fiery overthrow, the five cities of the Plain were conquered by an alliance of four northern kings led by Chedorlaomer of Elam who were in turn pursued and defeated near Damascus by Abram and his own private army. The record is rich in geographical data, as is the account of Israel’s crossing the southern Jordan Valley on their way into Canaan some four hundred years later. Both stories help to fill out the ‘dossier’ on Sodom’s location and must be taken fully into account along with the details of the destruction.

Four Northern Kings

David Barrett of the Bible Mapper blog recently posted about “The Battle at the Valley of Siddim.”[1] His map came just in time for me to correct a section of my dissertation on the geographical regions of the Israelite journeys for which I had to consider the Genesis 14 campaign amongst other biblical data.

Until seeing Barrett’s map, I had accepted Aharoni’s view that the four northern kings, having conquered the Amalekites at Kadesh, took the road ENE through Nahal Zin to the northern Arabah and thence northward to engage the king of Sodom and his allies in the Ghor (“sunken plain”) south of the Dead Sea.[2] The Zin road was an ancient highway, lately called in Arabic the Darb es-Sultan,[3] so this route seemed most likely. Ein Hazeva (Ain Husb) in the northern Arabah, sometimes identified as Classical Thamara,[4] is an awkward match for biblical Hazazon-Tamar because it lies some 15 km south of Nahal Zin’s entrance into the Arabah. In line with the northern kings’ route from Kadesh to the Dead Sea, Hazazon-tamar is often identified further north at Ein Tamar (Ain el-Aros, “spring of the palm tree”) [5] in the alluvial fan of Nahal Zin at the edge of the Sedom salt marsh. [6]

If, instead, Hazazon-tamar is En-gedi according to 2 Chronicles 20:2, there is a logical problem with the campaign sequence. Approaching from the south, En-gedi on the western side of the Dead Sea lies well past the traditional locations for the cities of the Plain, so that the invaders would have to turn back in order to do battle with the five kings. Moreover, the need for the king of Sodom to come out to battle if the invaders had already passed him by seems doubtful.

Messengers came and told Jehoshaphat, “A great multitude is coming against you from Edom, from beyond the sea; already they are in Hazazon-tamar” (that is, En-gedi). – 2 Chronicles 20:2

Barrett’s suggestion that the invaders approached from the west through the Northern Negev directly to En-gedi made better sense. I communicated to him that I would be glad to not have to explain how the four kings traveling north through the Arabah could have arrived at En-gedi before attacking the five kings to the south of the Dead Sea. He explained how he took a whole new look at Genesis 14 after reading that the entire south basin of the Dead Sea was likely dry during this period.[7]

Barrett’s map represents a very new understanding of the event, as compared to the map he created for the 2010 Crossway ESV Bible Atlas placing Hazazon-tamar at one of the northern Arabah locations suggested for Classical Thamara.

His suggested route from Kadesh (Ein Qudeirat) to Hazazon-tamar (at En-gedi) enters and passes the length of the Northern Negev (the Beersheba and Arad basins) from southwest to northeast following the eastern section of the Way of Shur. This was the same route later taken by the twelve Israelite spies from Kadesh towards Hebron at Moses’ direction (Num. 13:2, 17-22). The spies then continued northward along the length of the Hill Country to Lebanon (v.21).

According to Barrett’s new route, the four northern kings of Abram’s [8] time bypassed Hebron, continuing northeastward over the Dead Sea escarpment and down to Hazazon-tamar at En-gedi. Having conquered all peoples in their path on both the Transjordanian and Negev sides of the Rift Valley, presumably to isolate Sodom from its neighbors, the allied army emerged on the southwestern side of the Dead Sea basin, ominously facing the cities of the Plain across the Siddim Valley.

I observed to David that after defeating Sodom and capturing Lot, the invaders would not have ascended to the Canaanite highlands (as shown in his blog post map) because there is no record of them conquering any Cisjordan nations, unlike in the Transjordan where their conquest of the indigenous nations of the plateau is listed by nation and capital (Gen. 14:5-7).

The narrative does not say that the four kings went through Salem (Jerusalem), only that Abram and his men returned that way after pursuing and defeating them near Damascus and recovering the captives and booty (vv. 17-24). So, the four northern kings, having achieved their objective in subduing the Sodom region, probably headed north along the west side of the Dead Sea and the Jordan Valley to Dan, returning to their kingdoms in the Upper Euphrates region [9].

David promptly created a new version of his map for me, changing the course of the four kings’ homeward journey. For the sake of comparison with his new proposed advance across the Northern Negev, he added the Wadi Zin road from Kadesh to the Arabah. On the Way of Shur he also marked the intermediate station Ruheibe, now Rehovot ba-Negev, which was the likely location of Elijah’s (much later) encounter with an angel one day’s journey into the wilderness south of Beersheba heading towards Mount Horeb (1-Kings- 19:1-8). We discussed the Laudien article, but Barrett did not relocate any of the five cities of the Plain, presumably for lack of archeological evidence.

The resulting map is both familiar and surprising; the Sodom civilization is in the traditional locale south of the Dead Sea but the Chedorlaomer expedition circumnavigates the whole Sodom district at a great distance, somewhat like wolves circling a herd. Most importantly, only this new route-proposal makes geographical sense of the connection between Hazazon-tamar and En-gedi.

Earthquakes!

The Dead Sea itself is a feature of the major Afro-Asian fault line which runs from Kenya northward through the Red Sea and its eastern finger (the Gulf of Aqaba) to the Arabah Valley, the Dead Sea, the Jordan Valley, the Sea of Galilee, and the Hulah Valley until it finally ends in Lebanon’s Beqah Valley.

The Rift Valley and its many branches have experienced numerous earthquakes during the biblical period.[10]. In the Hebrew Bible, earthquakes seem to have been a factor in the Red Sea crossing (Ps. 77:17-20; 114), the Sinai display (Ex. 19:18), the earth ‘swallowing’ Korah (Num. 16:31-33), the Transjordanian conquest (Judg. 5:4-5; Ps. 68:7-8), the Jordan River crossing (Josh. 3:15-17; Ps. 114), Jericho’s fall (Josh. 6:20), Elijah’s ordeal at Mount Horeb (1 Kings 19:11-12), and judgment on Israel and her neighbors (King Uzziah’s earthquake, Amos 1:1; 9:1; Zech. 14:5).

In the Greek Bible (supported by numerous Hebrew prophecies, e.g. Zech. 14:3-4), earthquakes accompany Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection (Matt. 27:50-51; 28:2), the Roman conquest of Judea, (Matt. 24:7), and the destruction of Babylon the Great as latter-day “Sodom” (Luke 17:29-30; Rev. 11:13; 16:18; 18:17-18).

The divine intervention policy throughout biblical history seems to be “Never let a good earthquake go to waste.” Why should the cause of Sodom’s destruction—the original natural disaster of the long Hebrew saga—be an exception?

The Destruction of Sodom

The traditional explanation for the destruction of Sodom involves an earthquake in the Rift Valley causing a subterranean explosion that ignites the bitumen and rains burning sulfur and salt on the surrounding region (cf. Deut. 29:23; Luke 17:28-29).

The combustion of large deposits of stored hydrocarbons possibly created a subsidence (sinking) in the region, followed by a longterm increase in the level and extent of the Dead Sea, with hyper-salinated water thereafter covering any evidence of ancient towns.

As four of the five cities of the Plain were totally destroyed during this event, it is reasonable to conclude that Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboiim were all within the south basin of the Dead Sea although the latter two are not mentioned by name in the context of the destruction. Both the north and south basins of the Dead Sea have continued to subside.[11]

Bitumen, sulfur, and salt are evident mainly along the southwestern side of the Dead Sea; in fact, Har Sedom (the name preserved in the Arabic as Jebel Usdum) is an 11-km long salt dome. In this region the salt pillar popularly known as “Lot’s wife” overlooks Highway 90 which runs north-south along the Dead Sea’s western shore.

Laudien notes that such deposits are not to be found in the north or south-east of the Dead Sea region.[12] As Albright concludes, “The only possible location for the Vale of Siddim, with its asphalt wells (rendered “slime-pits” in the AV) is in the southwestern part of the Dead Sea.” [13]

The details of the Genesis story emphasize the proximity of Zoar to Sodom (Gen. 19:17, 25, 28). Having fled Sodom just before dawn, Lot and his daughters arrived at Zoar shortly after sun-up (19:15, 17-23). Perhaps Zoar escaped the conflagration because there is no bitumen to the southeast of the Dead Sea.

Salt domes often indicate subterranean reservoirs of trapped natural gas.[14]From the biblical description, Wood concludes that the means of Sodom’s destruction was an explosion and fire-storm:

“A possible explanation for the destruction of the Cities of the Plain is that pressure from an earthquake caused underground flammable petroleum products to be forced up through the fault lines. They then become [sic] ignited and rained down on the surrounding countryside.”[15]

Wood also notes that the specific words for “smoke” קִיטֹר qiytor and “furnace” כִּבְשָׁן kivshan indicate a strong upward draft typical of that from a flue (Gen. 19:28). It is important to note that the details of sulfur and fire (burning material) raining from above and thick smoke being forced upwards does not match the instant vaporizing effects of a superheated ‘flash’ of the type proposed by Collins and his colleagues.

If one is to locate and explain an event according to the biblical account, then surely all biblical data must be accommodated in the hypothesis.

Bill Schlegel, author of the Satellite Bible Atlas,[16]says:

I believe we will always have problems trying to locate Sodom and Gomorrah. Besides significant geological/geographical changes to the region associated with the divine destruction (Gen. 13:10), the divine destruction probably didn’t leave much (any?) of the cities to be found. The Hebrew for these cities’ destruction is unique (a combination of shachet “destroy” and hafach, “turn upside down”). It is unlikely that any of these tells/ruins in the Rift (north or south) are Sodom or Gomorrah. More likely is that these ruins represent peripheral cities, perhaps one was Zoar, which were spared the divine judgment.[17]

On the Other Hand…

There are some ‘cons’ for the traditional scenario, some logical, some chronological:

1. The level of the Dead Sea has receded substantially in recent years, causing the south basin to shrink. Extensive exploration and activity in the area has produced no evidence to indicate ancient sites.[18]It is possible, however, that the constant deposit of salt and silt via the incoming rivers has covered the valley bottom since ancient times.[19]

2. So far as historical records reveal, and despite numerous earthquakes along the Rift Valley over the biblical period, a cataclysmic event of the type reported in Genesis 19 has not happened again. This could simply indicate that the subterranean fuel was largely exhausted in the Sodom conflagration, or that other necessary conditions such as earthquake and climate have not coincided.

3. The leading candidates for Sodom and Gomorrah on the southeastern side of the Dead Sea—Bab adh-Dhra and Numayra—were destroyed in a firestorm at the end of the Early Bronze Age III, too soon for Abraham’s era in the Middle Bronze I according to the standard chronology.[20] As for En-gedi on the southwestern side, there is evidence for only three major periods of settlement—Chalcolithic, Iron Age, and Roman—none of these matching Abraham’s time either. John Osgood explores the radical implications of identifying the Chalcolithic civilization of the northern Negev with the Amorites of Hazazon-tamar in Abraham’s lifetime,[21] a shift that would also would align the collapse of the Early Bronze Age II-III in both Cisjordan (Canaan) and Transjordan (the Bashan, Ammon, and Moab) with the Israelite conquest.[22]Such a proposal opens yet another controversial front in the Sodom debate. Suffice to say, neither scenario has the support of conventional archeology which considers the Chalcolithic era to be prehistorical, the EBA pre biblical, and the Iron Age to be Israelite (hence, long after Abraham’s time).

The Southern Jordan Valley and the Identification of Tall al-Hamman

Some 400 years after Abraham’s covenant, his descendants the Israelites returned from Egypt to Canaan via the Sinai and Transjordan (Gen. 15:13-16; Judg. 11:15-22). Their final campsite before crossing into Canaan was on the “plains of Moab,” “on the Jordan [of] Jericho” יְרֵחֽוֹ עַל־יַרְדֵּן al-yarden yeriho (Num. 26:3, 63; 31:12; 33:48-50; 35:1; 36:13), or “across the Jordan [of] Jericho” יְרֵחֽוֹ לְיַרְדֵּן מֵעֵבֶר me-ever le-yarden yeriho (Num. 22:1; Josh. 13:32), the latter reference also specifying “eastward” מִזְרָחָה mizrahah.

The location of their camp is triangulated between three points, all towns—Jericho, Beth-jeshimoth, and Abel-shittim (Num. 33:48-49). Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) lies on the west side of the southern Jordan Valley, while Beth-jeshimoth (the name preserved as Tall Azaymah) lies near the northern shore of the Dead Sea. Abel-shittim, therefore, best matches the location of Tall al-Hammam on the east side of the valley, almost directly opposite Jericho.[23]It is apparent that Israel confined their camp to the southernmost part of the valley, possibly because of Ammonites in the central Jordan Valley near the mouth of the Jabbok.

The term “plains of Moab” is a common translation of aravoth moav מוֹאָב עַרְבוֹת, a steppe area above the floor of the Jordan Valley up to 8 km wide with an elevation from 300-200 m bsl. There are corresponding “plains of Jericho” on the other side of the Jordan (Josh. 4:13; 5:10; Jer. 39:5; 52:8; 2 Kings 25:5), somewhat narrower and irrigated by fewer perennial rivers. The Jordan River between them runs from about 380-390 m bsl.

The banks of the riverbed, dubbed by the prophets geon ha-yarden הַיַּרְדֵּן גְאוֹן “the pride of the Jordan” (Jer. 12:5; 49:19; 50:44; Zech. 11:3), sustain deep thickets of tamarisk, willow, poplar, oleander, cane and reeds. Between the lush river banks and the “plains of Moab” on one side and the “plains of Jericho” on the other side are several kilometers of high eroded mounds of barren חַוָר havar Lisan Marlstone.[24]

Altogether, the southern Jordan Valley is 22 km at its widest point from the arrival of Wadi Qelt in the west (hence Jericho) to the arrival of Wadi Sir-Kafrayn in the east (hence Abel-shittim), and about 20 km long from the alluvial fan of Wadi Shuayb in the north to the Dead Sea shore in the south.

This low-lying sunny watered region has much evidence of human habitation from earliest times. Scripture frequently alludes to the “beth-/baal-” cultic sites on the eastern slopes of the southern Jordan Valley: Bamoth-baal (Num. 22:41; Moabite Inscription [MI], line 27); Beth-/Baal-peor (Deut. 3:29; 4:46), Beth-jeshimoth (Josh. 13:18-20; Ezek. 25:9); Beth-/Baal-meon (Num. 32:37-38; Jer. 48:1, 23; Ezek. 25:9; MI, lines 9-10) and Beth-arabah on the Jordan river (Josh. 15:61).

To these may be added the names of towns in and around the southern Jordan Valley from all eras: (Abel-)Shittim (Num. 33:49; Josh. 2:1), Kiriathaim (Num. 32:37; Josh. 13:19; MI, lines 9-10), Elealeh, Sibmah/Sebam, Nebo (Num. 32:3, 37; Isa. 16:9; MI, line 14), and, on the western side, Jericho (e.g. 2 Kings 2:5).

So it is telling that not once in the biblical records of Israelite activity in, and travel across, the southern Jordan Valley (e.g. 2 Sam. 17:16; 2 Kings 25:5) do the texts refer to any of the five cities of the Plain, not even in a form such as “the place that once was known as Sodom” or “the fields of Gomorrah.” In the historical geography of Israel and Jordan, the absence of evidence does, in fact, count towards evidence of absence, for the region is small, the biblical traditions draw long threads, the data is extensive, and many names are preserved in Arabic to modern times.

Conclusion

Whatever the historical truth regarding a meteor strike and airburst at Tall al-Hammam, Sodom was not in the southern Jordan Valley. The case for locating the five cities of the Plain to the north of the Dead Sea is in conflict with the wider scenario. According to biblical geographic data, Sodom lies south not east of Jerusalem (Ezek. 16:46), close to the site of Zoar (Gen. 19:20-22), and within view of Hazazon-tamar at En-gedi on the western shore of the Dead Sea (2 Chron. 20:2).

Byzantine and Medieval evidence for the location of Zoar on the southeast side of the Dead Sea makes good sense with the Genesis story. So also does the Chronicles identity of Hazazon-tamar at En-gedi on the southwest side (2 Chron. 20:2 cf. Gen. 14:7-8), a detail concordant with the early historians who consistently connect En-gedi with the region of Sodom.

Laudien’s support of the Classical view and Barrett’s epiphany regarding the route of the invaders from Kadesh to Hazazon-Tamar together account for all the biblical, historical and geographical data, if not the archeological data thus far known.

Collins proposed identifying Sodom as Tall al-Hammam around 2009. Realizing that the likelihood of bituminous conflagration in this region was low or absent, he and his colleagues went on to propose an alternative cause of catastrophic destruction. However, their meteoric air-burst hypothesis seems far less likely than a hydrocarbon explosion caused by a seismic event.

With the abundant presence of bitumen, sulfur and salt in and around the south basin of the Dead Sea, and with the passing of the great Afro-Asian fault-line through the center of the Rift Valley, there is no need to postulate another type of cataclysm. Tall al-Hammam is almost certainly the biblical town of Abel-shittim, one of many cities destroyed at the end of the Middle Bronze Age throughout Israel and Jordan.

Collins and his colleagues’ theory of a meteoric airburst does not account for several specific details of the biblical account: the raining of burning material, sulfur and salt; the location of the bitumen deposits; Zoar’s escape despite its proximity to Sodom; and Hazazon-tamar’s identity at En-gedi. When presented with competing hypotheses explaining the same event or effect, one should select the solution that meets the most criteria while relying on the fewest assumptions.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

END NOTES

[1] David P. Barrett, “The Battle at the Valley of Siddim,” Bible Mapper (blog), July 19, 2021, https://biblemapper.com/blog/index.php/2021/07/19/the-battle-at-the-valley-of-siddim/.

[2] Yohanan Aharoni, “Tamar and the Roads to Elath,” Israel Exploration Journal 13, no. 1 (1963): 31-34.

[3]C. Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence, The Wilderness Of Zin (Archaeological Report), vol. 1914–1915, Annual (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1914), 71.

[4] Aharoni, “Tamar and the Roads to Elath.”

[5] With palms common from Jericho to Zoar (Deut. 34:3), the name is not indicative of the biblical site. In the Mishnah, Zoar is called ‘the City of Palms’ (Yevamot 16, 6).

[6] Yizhar Hirschfeld, “The Nabataean Presence South of the Dead Sea: New Evidence,” in Crossing the Rift: Resources, Routes, Settlement Patterns, and Interactions in the Wadi Arabah, ed. Piotr Bienkowski and Katharina Galor, Levant Supplementary Series 3 (Oxford: Oxbow, 2006), 170.

[7] David Neev and Kenneth O. Emery, The Destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah, and Jericho: Geological, Climatological, and Archaeological Background (New York: Oxford University, 1995), 62.

[8] Later renamed Abraham (cf. 17:5).

[9] Perhaps Melchizedek met and blessed Abram in thanks for preventing the northern kings from entering Canaan.

[10] Gary Byers, “Jordan River Valley, Jordan River and the Jungle of the Jordan,” Associates for Biblical Research, June 6, 2007, https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3844-the-jordan-river-valley-the-jordan-river-and-the-jungle-of-the-jordan.

[11] Neev and Emery, Destruction of Sodom, Gomorrah, and Jericho, 123–24.

[12] Marcus Laudien, “Sodom and the Dead Sea,” The Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 9 (2002): 88.

[13] William F. Albright, “The Archaeological Results of an Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 14 (1924): 9.

[14] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/salt-dome

[15] Bryant G. Wood, “The Discovery of the Sin Cities of Sodom and Gomorrah,” Associates for Biblical Research 12, no. 3 (Summer 1999): 67–80.

[16] William Schlegel, Satellite Bible Atlas: Historical Geography of the Bible (Israel, 2012).

[17] Bill Schlegel, “Biblical Problems with Locating Sodom at Tall El-Hammam,” BiblePlaces (blog), January 4, 2012, https://blog.bibleplaces.com/2012/01/biblical-problems-with-locating-sodom.html.

[18] Primary sources are detailed in: Wood, “Discovery of the Sin Cities.”

[19] Albright, “Expedition to Moab and the Dead Sea,” 8.

[20] Wood, “Discovery of the Sin Cities.”

[21] A. J. M. Osgood, “The Times of Abraham,” EN Tech 2 (1986): 77–87 https://creation.com/the-times-of-abraham.

[22] A. J. M. Osgood, “The Times of the Judges—The Archaeology: (A) Exodus to Conquest,” Journal of Creation 2, no. 1 (April 1986): 56–76 http://creation.com/the-times-of-the-judges-the-archaeology-exodus-to-conquest.

[23] For a compilation of references, see David E. Graves and Scott Stripling, “Identification of Tall El-Hammam on the Madaba Map,” Biblia | Sermons and Biblical Studies (blog), accessed October 29, 2021, https://www.biblia.work/sermons/identificationof-tall-el-hammam-on-the-madaba-map/.

[24] Menashe Har-El, “The Pride of the Jordan: The Jungle of the Jordan,” Biblical Archaeologist 41, no. 2 (1978): 67–68.

TOP PHOTO: Sodom and Gomorrah Afire by Jacob de Wet II, 1680. (credit: Daderot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

NOTE: Not every view expressed by scholars contributing Thinker articles necessarily reflects the views of Patterns of Evidence. We include perspectives from various sides of debates on biblical matters so that readers can become familiar with the different arguments involved. – Keep Thinking!